First, labyrinths

are often connected

with fertility through stories in which they are the scene of meetings

in springtime between male and female, or earth and sky deities, thus

beginning

each year’s new cycle of vegetation and growth.

Second, the roadway suits

wagon ceremonies,

such as of the fertility goddess in the wagon described by

Tacitus.

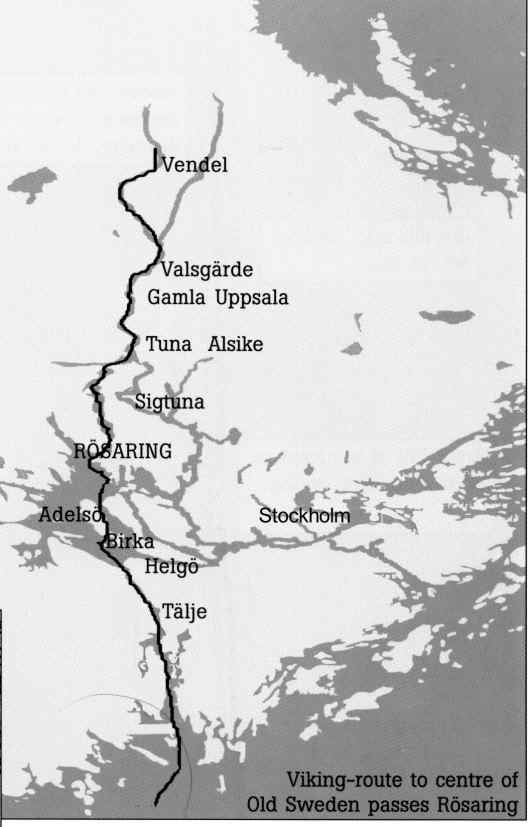

Third, place names in the

neighbourhood

also call attention to a fertility cult. About 5 km from Rösaring

we find the names Härnevi and Ullevi, which refer to the female

earth

goddess Härn (Nerthus) and her male counterpart Ull, a sky god,

both

from the period before the Viking Age. A similar pattern of place names

is to be found near all labyrinths lying on ridges crossing Lake

Mälaren,

as shown by John Kraft in a book published by UKF in 1999.

The labyrinth

The labyrinth at Rösaring was associated

with ancient

gods already in 1684, when Hadorph, known as the “father” of Swedish

antiquarian

research, wrote: “… on a high hill … where there is a Troijenborg

...

there has been much sacrifice to the gods in olden days”.

Labyrinths in Sweden have long been called

“Trojeborg”

(City of Troy), pointing to a link with Mediterranean countries, where

such labyrinths were common before the Roman Empire. The Minoan culture

of Crete even used labyrinths as symbols on their coins. Beside the

labyrinth

on the famous Etruscan vase from Tragliatella is written a name meaning

Troy. Full scale or field labyrinths in these countries have not

survived.

There are some turf examples elsewhere in Europe, but today the

majority

of field labyrinths are in Scandinavia. Here they tend to survive more

readily, being built of stones in a sparsely populated country. Most

Swedish

labyrinths are near the coast, built during recent centuries for quite

different reasons to the 20 or so labyrinths found inland on ancient

sites,

such as Rösaring.

|

|

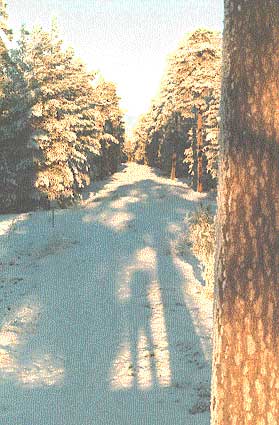

| Photo 1. Looking south toward the

flattened mound

at noon on midwinter day. Photo Börje Sandén |

Typically, these labyrinths have only one path

leading

to the centre - a round, winding pathway defined by 8, 12 or 16 rings

of

small stones. Mazes with blind paths did not appear until the 15th

century.

The historical form of

labyrinths

is said to be a symbolic city or castle, (borg in Swedish) from which a

woman had to be liberated. The Homeric story of a ten-year siege to

free

the fair Helen of Troy may be a relatively recent tale, based on the

original

ancient myth in which the woman in question was a fertility divinity,

to

be delivered with symbolic rites from her winter prison at the start of

spring. We do not know for certain how this was done - no doubt it was

in many different ways in various places and times, according to tales

from all over the world. It is worth noting that in the church of Sibbo

in Finland, a picture of a labyrinth includes a girl at the centre.

|